Miasma Protoplasma

25. June – 25. July 2021

Aldea, Center for Contemporary art, Design and Technology, Bergen

Documentation: Dale Rothenberg26. August – 19. September 2021

BO, Oslo

Documentation: Adrian Bugge11. march 2022 — 10. april 2022

Platform, Stockholm

Documentation: Lou MouwCurator: Cameron MacLeod

Text: Anthea Buys

Review: Hygienens attraksjon, Victoria Durnak, Kunstkritikk

Interview: I en sammensmelting av maskiner og anatomisk uro, Hedda Grevle Ottesen, BO

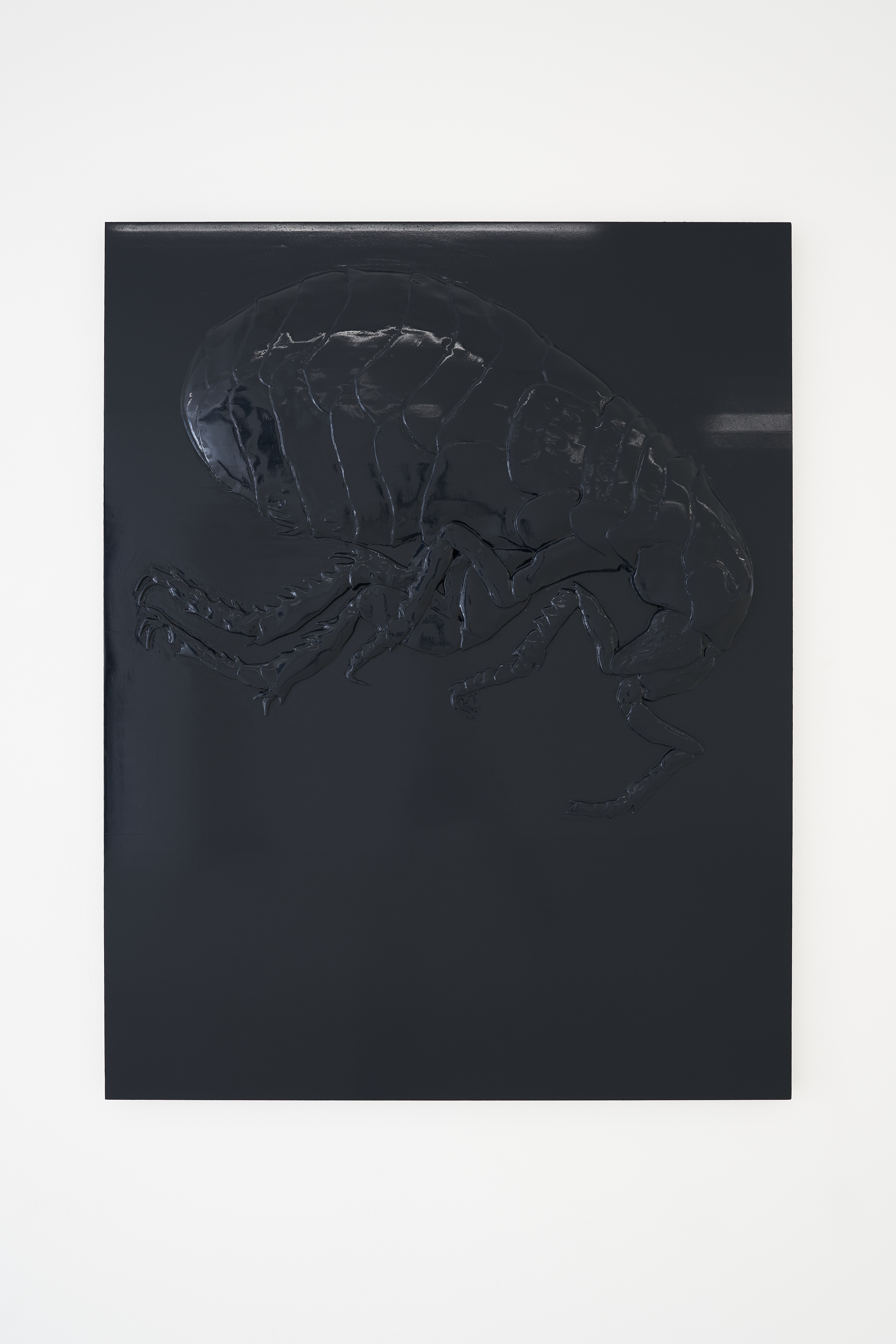

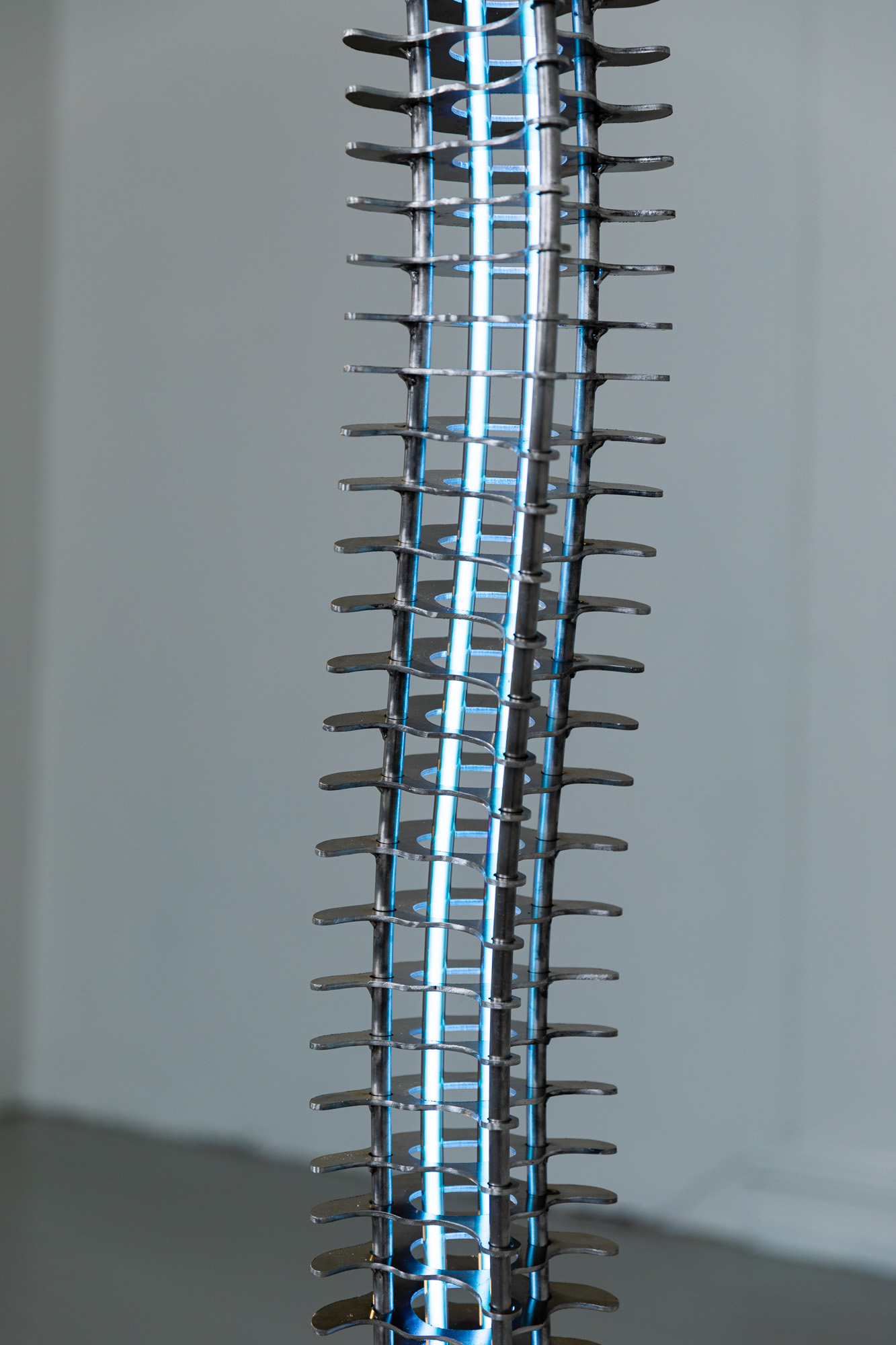

Miasma Protoplasma describes a parallel existence where historical ideas about disease and contagion manifest as an alienated environment. Referring to the miasma theory, which explained airborne disease before the paradigm of microbiology as a death bringing mist and disease carrying air, the show consists of sculptures assuming the form of bloodsucking animals and cyborg associative objects. The works explore handmade processes and traditional sculpting mediums in relation to digital sculpting, combining materials like aluminium, various 3D-printed filaments, blown glass, casted concrete, CNC-milled wood fibre, hand built ceramics and manufactured neon. By combining physical and virtual sculpting the works use disparate models of object understanding as a method of addressing the body in relation to an invisible health threat and uncertain environment; navigating through overlapping theories and conflicting constructs.

Flash fiction written for the exhibition by Anthea Buys:

The RoomOn the seventh of fourteen sweaty nights – the heatwave was unrelenting – I found the room you’re standing in now. It wasn’t empty, but it wasn’t full either. Eight objects lay on the floor in the dark. It was my job to find one of them, although I didn’t know which.

The room, as you know, is in the basement of what might have been the town’s hospital. Like the churches and the grocery stores, hospitals belonged to a bygone time, a time out of joint with the present we know.

On the first and second floors rows of metal bed frames still line the halls. The later hospitals all favoured this layout, itself a revival of the field hospitals of the twentieth century’s great wars, because by that time the notion of contagion was largely irrelevant. Everyone was already sick. Everyone had made everyone else sick. They – the doctors, the politicians, the people – had just begun to accept that bespoke medical attention was an outdated, even fanciful notion.

Today these halls are materially homogenous, braids of concrete, metal and plastic. The mattresses and bedding belonging to the rows of beds have long since vanished. Every few beds there is a tree-like metal stand whose hooks sometimes have empty plastic sacks hanging from them. Tiny needles lie in clusters where the floor meets the walls as if swept there, perhaps at the time that the landfills were declared full, which was about the same time as the incineration of medical waste was banned.

The higher floors of the building are inaccessible. The elevator shafts are filled with debris up to the first and sometimes even the second floor, and the entrances to the flights of stairs have been bricked shut.

The basement has the same footprint as the first and second floors, but a much lower ceiling. If you jump you should be able to touch it with no difficulty. The room is engulfed by complete and palpable darkness, darkness of the sort your eyes simply can’t tolerate, blindness. To find the objects I had to crawl on my hands and knees, although I first encountered one by bumping into it. The objects were interspersed in the environment and seem placed rather than strewn. They were all hard and cold to the touch, round in some parts, sharp in others, maybe delicate – it’s impossible to say.

When you really want to find an object you have to look with your eyes closed. So the darkness of the room was not an impediment to my search. On the contrary, it forced me to circumnavigate the visual instinct and reach instead for something postural, latent in the body, a secret communication from vessel to vessel.

After the night that I found the room, I returned to it four times, each on a separate night, each night seemingly hotter and longer than the night before. Each time I thought I came closer to finding the object, but the heat and the thickness of the air brought on in me an overwhelming fatigue and I had to stop before sunrise. By the fourth night, my body had become a fluent reader of the text of the room, and it knew with some confidence the distances between objects, their textures and volumes. But on that night, my body found the room empty. I crawled across the breadth of the room, snaking my way back and forth, and wherever an object had been there was nothing but a small cloud of cold air and a dampness on the ground.

I left perplexed. Perhaps I had simply run out of time. The heatwave ran its course and I didn’t return to the room.