Suckers at the base of the main stalk

12. September – 06. October 2024

Bærum Kunsthall, Oslo

Documentation: Tor S. Ulstein / Kunstdok

Phytosleep

19. – 29. September 2023

Studio PRÁM, Prague

Curator: Šárka Koudelová

Documentation: Filip Švácha

The exhibition Phytosleep was the result of a two month residency at Studio PRÁM, Prague

Exhibition text written by curator Šárka Koudelová

The word “synthetic” does not in itself mean more than “put together” or “made up of several parts”. Yet we subconsciously perceive it as a negative quality, a toxic opposition to our dream kalokagathia. Conversely, anything with the label “natural” or “organic” is perceived as the best for the human body, soul and moral profile. But what are the real meanings of these words, aside from capitalist marketing, in the context of the so-called chemical Anthropocene, about which the theorist Lenka Veselá writes1? The term Anthropocene has come to mean an epoch in which the consequences of human activity have caused irreversible changes in the planetary ecosystem. The chemical Anthropocene can then refer to the era when human and any other cells were colonized by the emissions of industrial production. Chemicals that affect hormone production have become an integral part of metabolism, affecting our mood, lifespan and reproduction.

In her new series of works, most of which are surprisingly painterly given her exclusively sculptural focus, Linda Morell processes her own surprise at the banana’s form before its domestication. The banana – a humorous sexual metaphor – and yet it has been stripped by man of its own capacity for sexual reproduction. The seeds inside the fruit unnecessarily took the place of the sweet flesh and had to give way to our vision of a healthy natural snack. Imagining a healthier self, we reach for seedless fruits in the supermarket and guaranteed organic supplements in the pharmacy to give us more energy for our stressful lives and to relieve our environmental grief. In the context of the theory of the chemical Anthropocene, Linda inquires herself about the meaning of the glorification of health, “clean” raw materials in a polluted world, and explores the possibilities of rearranging plant and human life forms.

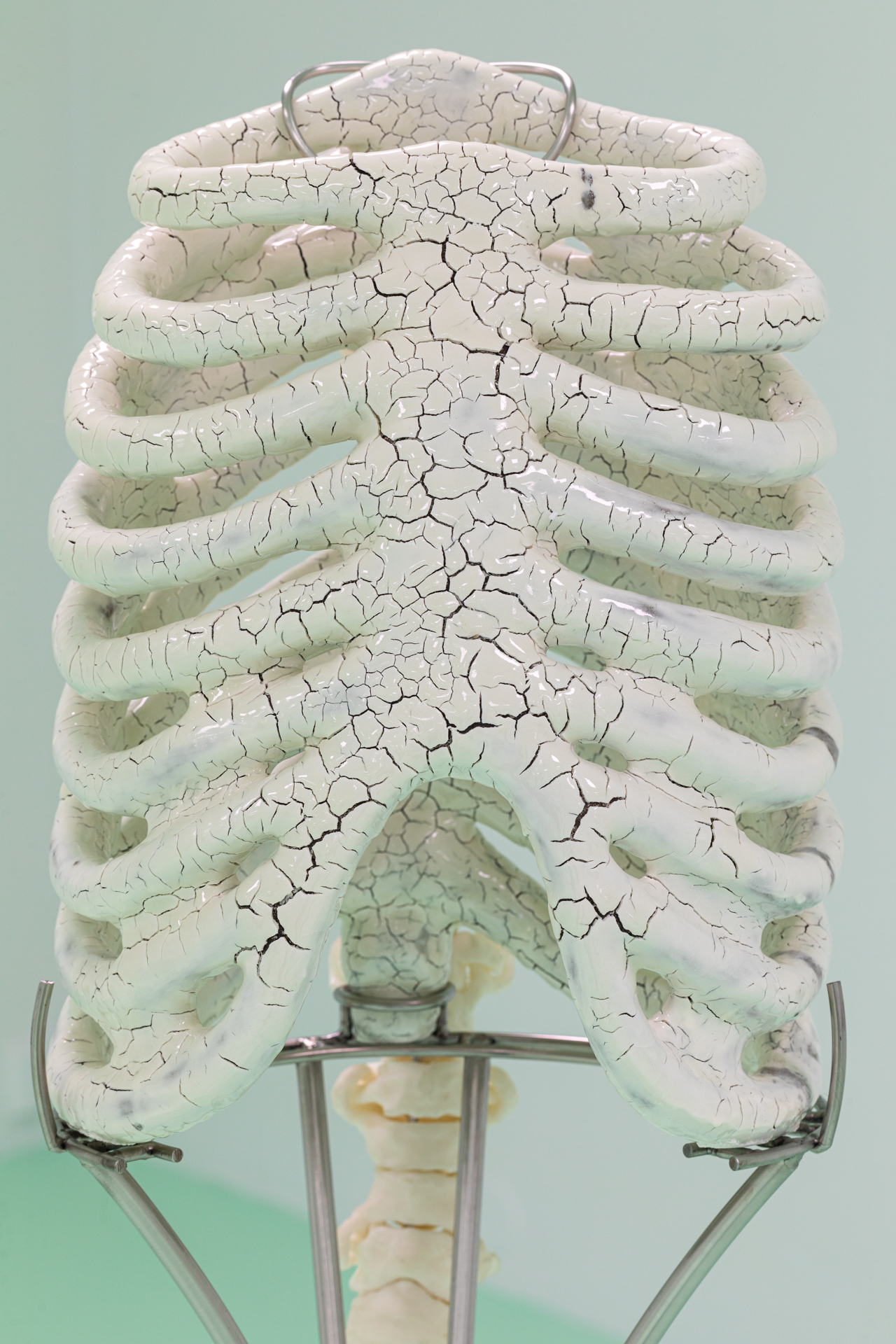

Plant bodies, which we have cut off from the possibility of evolution by domestication and control of their reproduction, cannot synthesize with the new conditions. Do we accept that new human bodies synthesized with bypasses, implants, anti-age methods, added hormones or queer modifications can be natural?

Aloe vera, with which we potentially share much of our bodies in the planet-wide water cycle, is perhaps the absolute best-seller of natural products. Its leaf, with whose skin, succulent flesh and morphology we readily identify, lies ready on the ambo, dominating the space of the exhibition, to wither solemnly and be devoured by parasitic tendrils.

The entire installation is bathed in a yellow light, the hue of which seems exactly on the borderline between soothing and toxic waste. Linda Morell thus intuitively connects the current social atmosphere of reconciled limbo with the anxious anticipation of catastrophe. The situation suggests that even the threat of extinction will not change human habits. However, our species position, built on the exploitation and control of other species, obliges us to at least make a conscious effort to emancipate ourselves from the industries that non-consensually controls the lives of all earthly beings at the molecular level. The beginning of liberation is the change of the obsolete idea of the “naturalness” of our bodies.

1Veselá Lenka, Chemický antropocén, Flash Art #66, 12/2022 – 3/2023

Czech & Slovak Edition [online], zdroj: https://flashart.cz/2023/02/02/chemicky-antropocen/

Documentation: Linda Morell

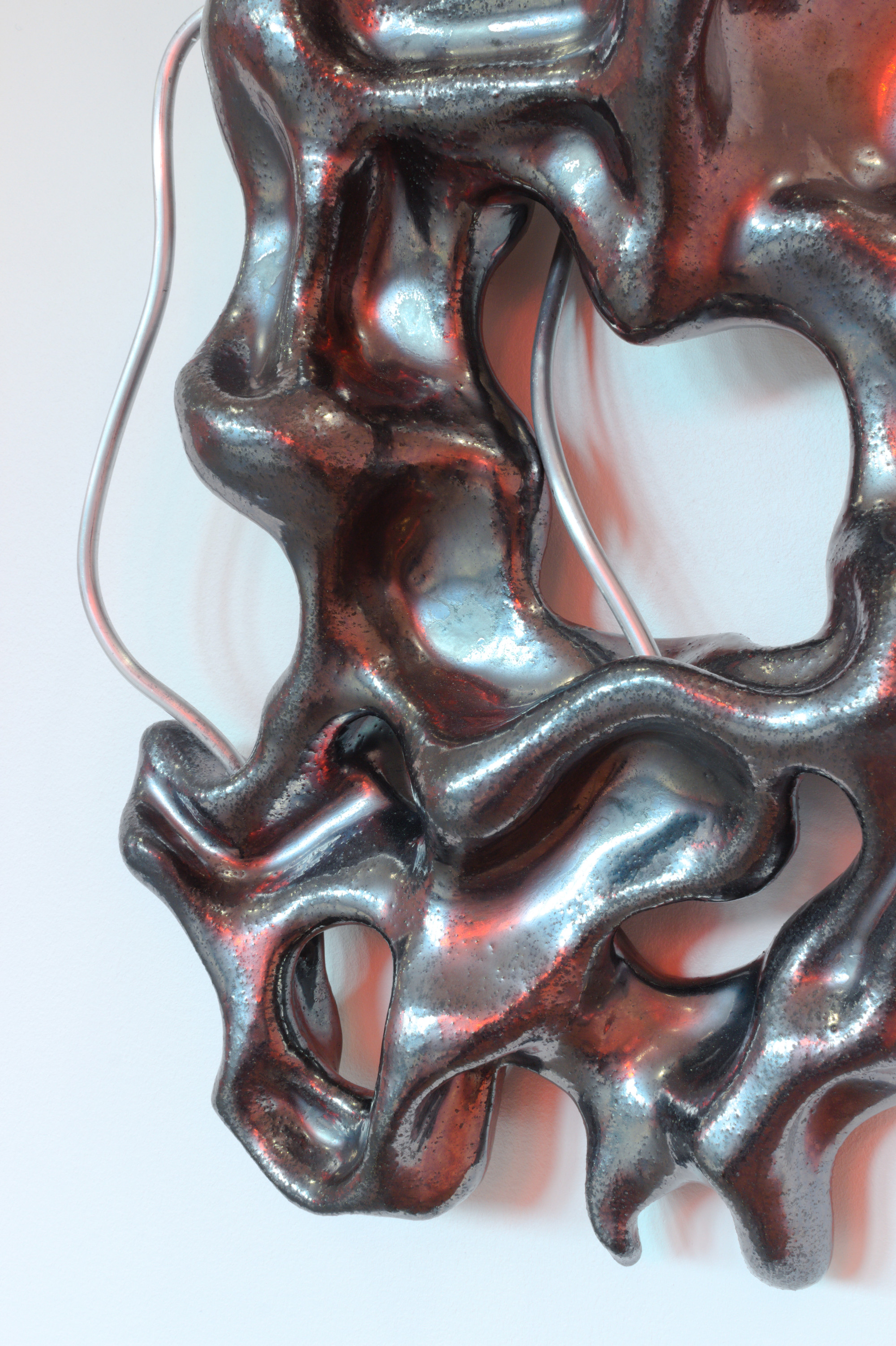

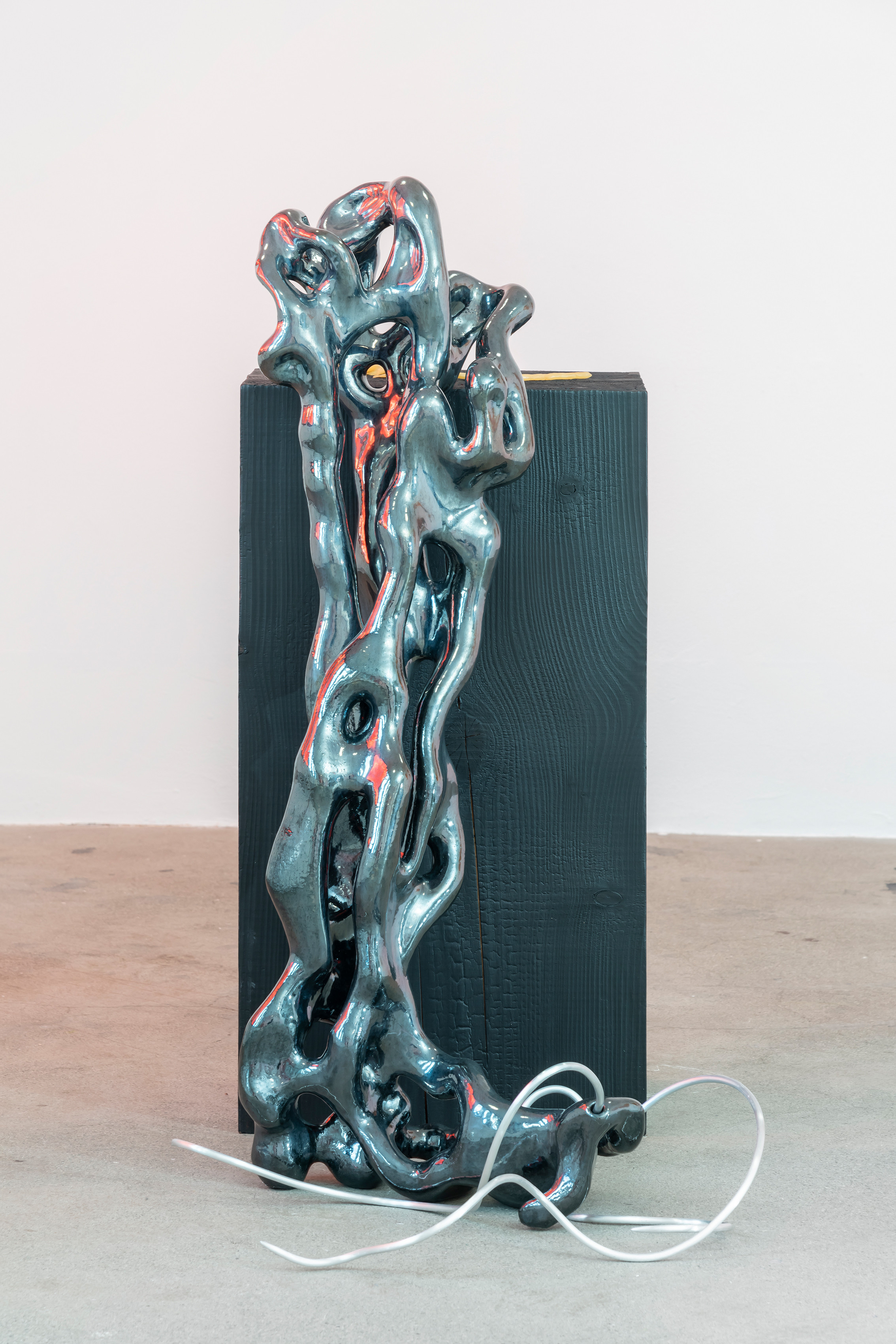

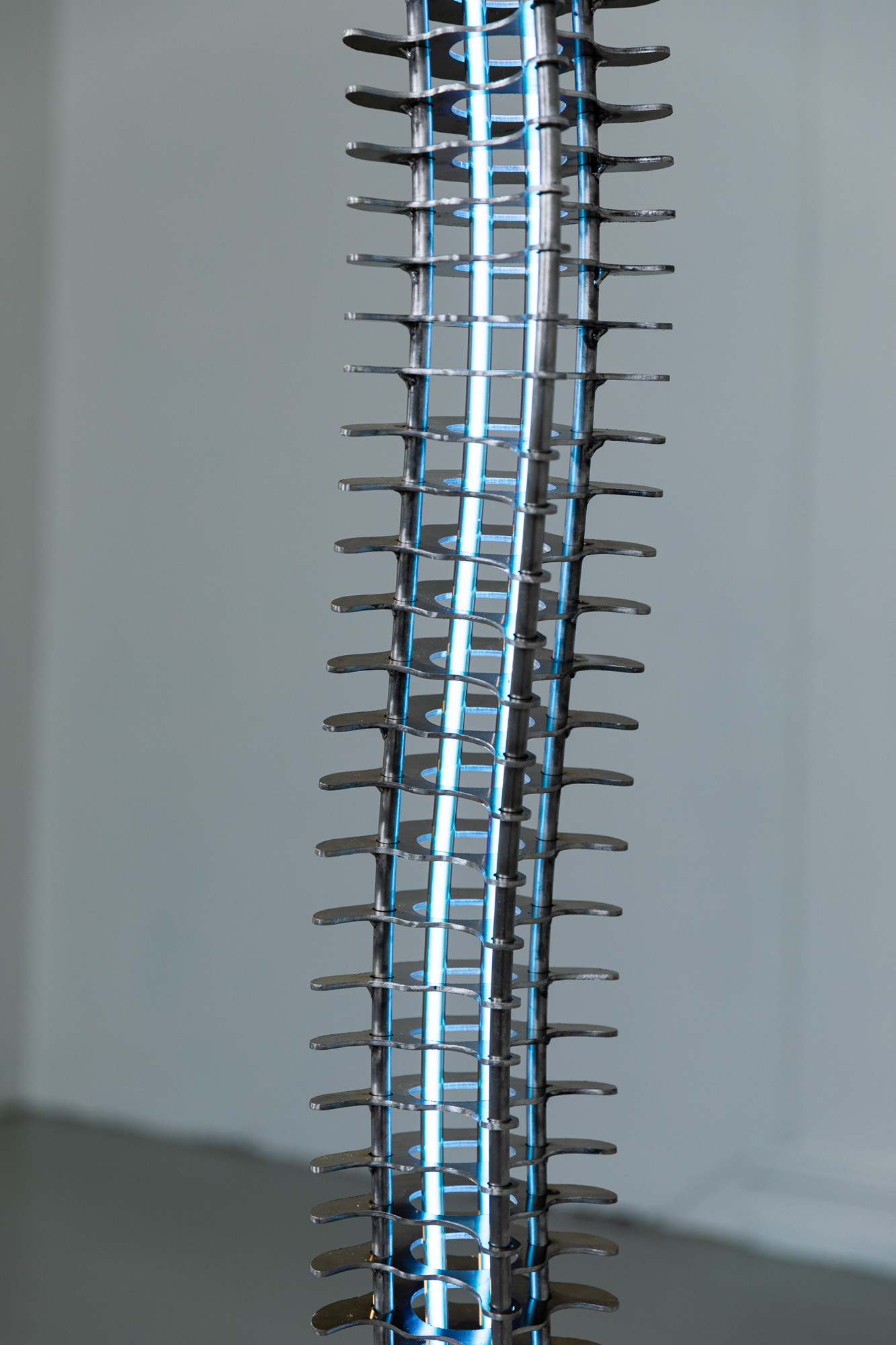

Oil nebula

Oppland Kunstsenter, Lillehammer, 2022

Vestfold Kunstsenter, Tønsberg, 2022

S12, Bergen, 2023

Documentation: Øystein Thorvaldsen, Linda Morell

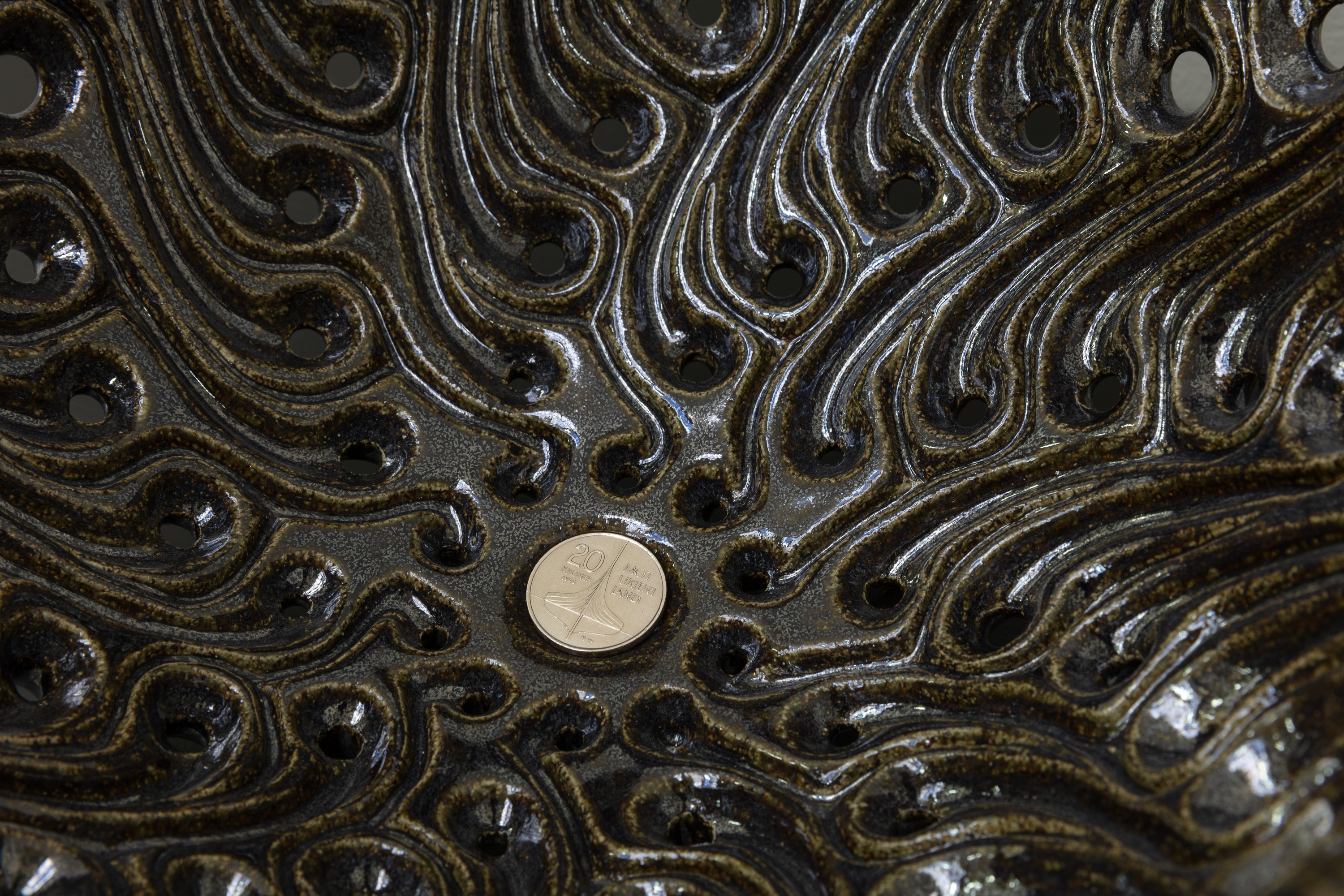

The exhibition Oil nebula uses the concept of the abyss, the vast cosmic sea as described in John Milton's Paradise Lost (1667) which separates earth from hell, as a metaphor for societal collapse. The project draws parallels to the jellification of the oceans, where ecosystems are changing and new organisms thrive. Inspired by the increasing prevalence of invasive species and environmental changes, the exhibition consisting of works in ceramics, glass, wood and aluminium strives to mythologize the defamiliarized earth. The works form a visual language which speaks about the future of the oceans and humanity whilst forming the inhospitable sea of the abyss itself. Like Milton’s abyss, simultaneously described as the worlds cradle and it's grave, the exhibition becomes an ouroboros focusing on both the perils and prospects of the future.